Educability, Opportunity, & Necessity: The Keys to Fairness in Education

[The following talk was presented in May, 2023 at the Annual General Meeting of the School Board Governance Association of New Hampshire.]

If we're going to make any significant changes to public schools, we need to change how we talk about public schools.

Right now, we talk almost exclusively about money, when we need to be talking about achievement.

The key to changing the conversation is changing how we think about fairness.

I've written a book about that. It’s called Rethinking Fairness in Education.

In this post, I’m going to use some ideas from the book to support some changes that we could — and should — make in education policy.

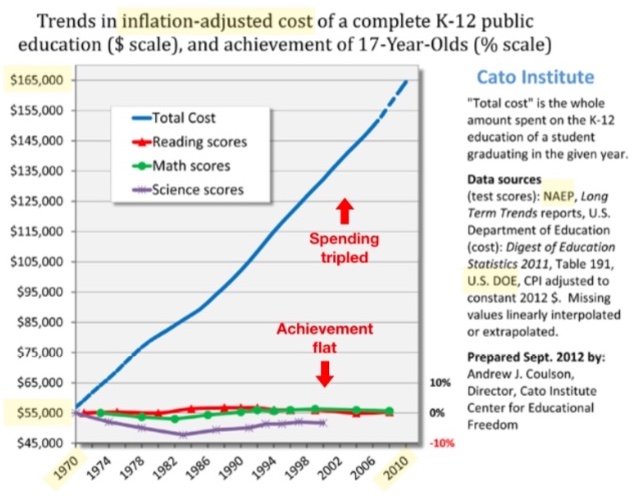

The first step towards shifting the conversation away from money is to realize that money is largely irrelevant. There are three graphs that make the case beyond any reasonable doubt.

The first graph speaks for itself. Over the course of half a century, we’ve tripled spending (adjusted for inflation), while getting no change in achievement — as measured by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), which is the test designed by the education establishment, to let us know how they’re doing.

The second graph is for the NAEP 4th grade reading test, but you can pick any test, for any grade, and it looks the same.

Each dot represents one state. Even though states spend anywhere between $7,000 and $25,000 per student, they all get about the same failing scores. The states with the highest scores like to say that they’re the best states for education. But really, they’re just the least worst.

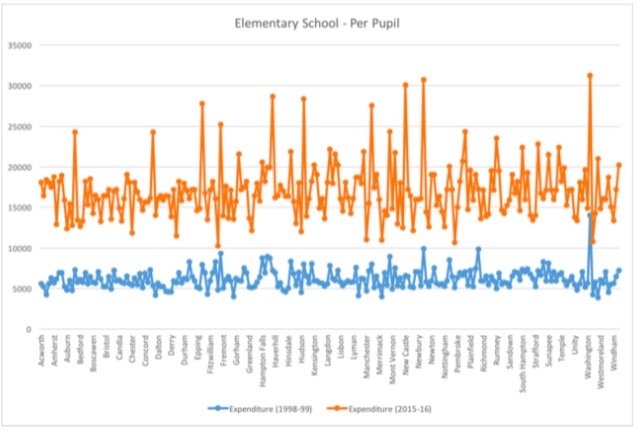

The third graph shows the fallout from the Claremont state supreme court cases at the turn of this century. On the bottom, in blue, we see per-student spending by district before Claremont. On the top, we see the corresponding figures twenty years later, adjusted for inflation.

School spending increased everywhere by an average of $10,000 per student per year. Did I mention that that’s adjusted for inflation?

This means that every district is now spending more than any district (except Waterville Valley) was before. In terms of spending, every district is a rich district. But they’re getting the same results as before: less than half of students performing at the most basic level of proficiency in reading and math.

The message of these graphs couldn’t be clearer: Unless we change what we do, it won’t matter how much we spend.

And yet, the public policy remains focused on money.

The legislature is debating bills that specify how much schools need for 'adequacy payments’ — which are based entirely on attendance, and not at all on achievement, adequate or otherwise.

School districts are back in court fighting over spending amounts, and taxing mechanisms.

But before we can figure out how much we should spend on something, we have to know what we're trying to do, and why.

I suggest that to answer these questions, we take seriously what our state supreme court said in their Claremont decisions:

The why is to ensure the preservation of a free government.

The what is to provide each educable child with an opportunity to acquire the knowledge and learning necessary to participate intelligently in the American political, economic, and social systems of a free government.

It's worth noting that whenever I quoted the court at a Croydon school board meeting, it was greeted with cries of

That's a crazy Free-Stater idea!

That's too small a vision of public education!

That's detrimental to society!

and so on. As if it was something that I just made up.

When I quoted the court to a journalist, she accused me of being 'an originalist'. Regarding a decision from 25 years ago! The mind reels.

In a nutshell, I'm suggesting that we take the court’s statements at face value, paying careful attention to the words educable, opportunity, and necessary.

Educable has never been defined — not in a court ruling, not in a statute, not in an education rule. Whatever else we mean by it, we could make a good first step towards sanity by saying that ineducability includes 'refusal to learn'. That is, any kid should be able to declare himself to be ineducable, thereby relieving his school district of the responsibility to provide him with anything.

Any child — any person, really — who has a high-speed Internet connection and a computer or smartphone has the opportunity to learn pretty much anything that there is to know. So really, a school district could drop its school costs by a factor of ten or more by saying to each child in the district:

Here is your Chromebook ($300), and here is your Starlink subscription ($100 per month). Oh, and if your parents don’t have a better plan, you can enroll at the Virtual Learning Academy Charter School (VLACS) for free.

Before dismissing this approach out of hand, I would ask you to consider a couple of crucial questions:

If a kid wants to learn something, who can stop him?

If a kid doesn't want to learn something, who can make him?

We all know the answers to these questions. How different would our schools be if we took them seriously?

But even if we completely ignore educability and opportunity, we can still do something about necessity. If participating intelligently in the systems of a free government requires you to know something, or to be able to do something, then it is necessary — and the court says the state is required — to provide an opportunity to learn it.

Examples would include being able to read a statute or business contract or credit agreement, identify a specious statistical argument, understand when advocacy is being presented as science, tell the difference between an insurance program and a Ponzi scheme, and so on.

On the other hand, if participating intelligently in the systems of a free government does not require you to know something, or to be able to do something, then it is not necessary, and the state is not required to provide an opportunity to learn it.

Examples would include being able to speak French, spike a volleyball, play the violin, weld two pieces of metal together, calculate a derivative or integral, and so on.

We can think of illiteracy, innumeracy, and irrationality as three 'diseases' that would prevent someone from participating intelligently in the political, economic, and social systems of a free government. When considering whether taxes may be used to teach some knowledge or skill, we can ask: Which of these conditions does it help 'cure'? If the answer is 'none', then the state supreme court has placed it outside the scope of tax-funded education.

In the book, I show how this framework can be used to pare down the current laundry list that passes for a definition of ‘adequate education’ in the public school system.

But today, I want to present an even simpler approach, which we could implement with a couple of simple rules, based on taking the court's direction seriously.

Basically, if something is to be learned by any student, it must be learned by every student. Consequently, if something is not taught at every tax-funded school, it must not be taught at any tax-funded school.

For example, unless all tax-funded schools can put together a band, or a football team, or a robotics club, then no tax-funded school can have those. Unless all tax-funded schools can provide courses in welding, or AP History, or drama, then no tax-funded school can have those. And so on.

There are a few things to say about this, to prevent it from being 'interpreted' to just mean what we're already doing now.

First, we have to distinguish between teaching and learning. If something is necessary, then every student must learn it, and be able to demonstrate that learning. It’s not enough that a student just be taught it.

Second, by 'something', I don't mean nebulous categories like 'technology', where that translates in practice to some kids learning how to set up an Excel spreadsheet, while other kids are learning how to design and program robots.

(If all kids need to learn to set up spreadsheets — if that's necessary for intelligent participation in the systems of a free government — then that's part of the public school curriculum. If not all kids need to learn to make robots, then that's not part of the public school curriculum.)

I mean competencies, like being able to read a policy argument and identify the logical fallacies that are being used to mislead the reader.

Third, people often think that focusing on fundamentals is somehow 'lowering the bar'. Tell that to Michael Jordan, who famously said, ‘Get the fundamentals down, and the level of everything you do will rise’.

On the contrary, I’m talking about raising the bar, to the point where kids are literate, numerate, and rational enough to take charge of their own educations, and take full advantage of the torrent of world-class, zero-cost pedagogy that is literally falling, 24/7, from the sky.

I'm talking about teaching them the skills they need to learn whatever content they want, whenever they want.

That would be, not just a good first step, but a giant leap in the direction of fairness in learning, as opposed to fairness in funding.

But even if we continue to focus on money, there is something we could do immediately that would almost certainly cause significant improvement in student achievement.

In the real world, we pay for things after we get them. First, the tires go on, and then the installer gets paid. First, the tumor is removed, and then the hospital gets paid. And so on. This is so familiar to so many of us that it almost seems silly to mention it.

Schools don't work this way. But they should.

That is, schools should be paid, after the fact, for achievement, rather than beforehand, for attendance.

We already have precedents for this.

For example, VLACS only gets paid when students actually learn something. Proficiency first, payment second.

More interestingly, the current model for 'adequacy payments' is that schools get money this year for average attendance last year.

So the model is already in place. We don't have to change who we take money from, or who we give it to.

We just have to change what we're paying for. And refuse to pay when we don’t get it.

That is, right now, we pay for attendance, and get attendance — and not much more. What would happen if instead, we paid for achievement?

What if schools only got paid after the students learned what we need them to learn?

As I put it in the book,

For students, fairness in education means: You get exactly the same adequate education as everyone else. No more, and no less. No matter who you are, or where you live, or what your parents can afford. And this takes as long as it takes.

For taxpayers, fairness in education means: Your taxes are used to pay for public benefit, but not for private enrichment, or political influence. And they are used to pay for results, not for time spent, or for good intentions.

What could be fairer than that?